Middle School Cross Country Training PDF

📌 KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Don't take high school training and "water it down" — middle school needs its own approach

- Many top college women weren't standouts in middle school; some never ran until high school

- Be especially conservative with middle school girls — no correlation between MS success and college success

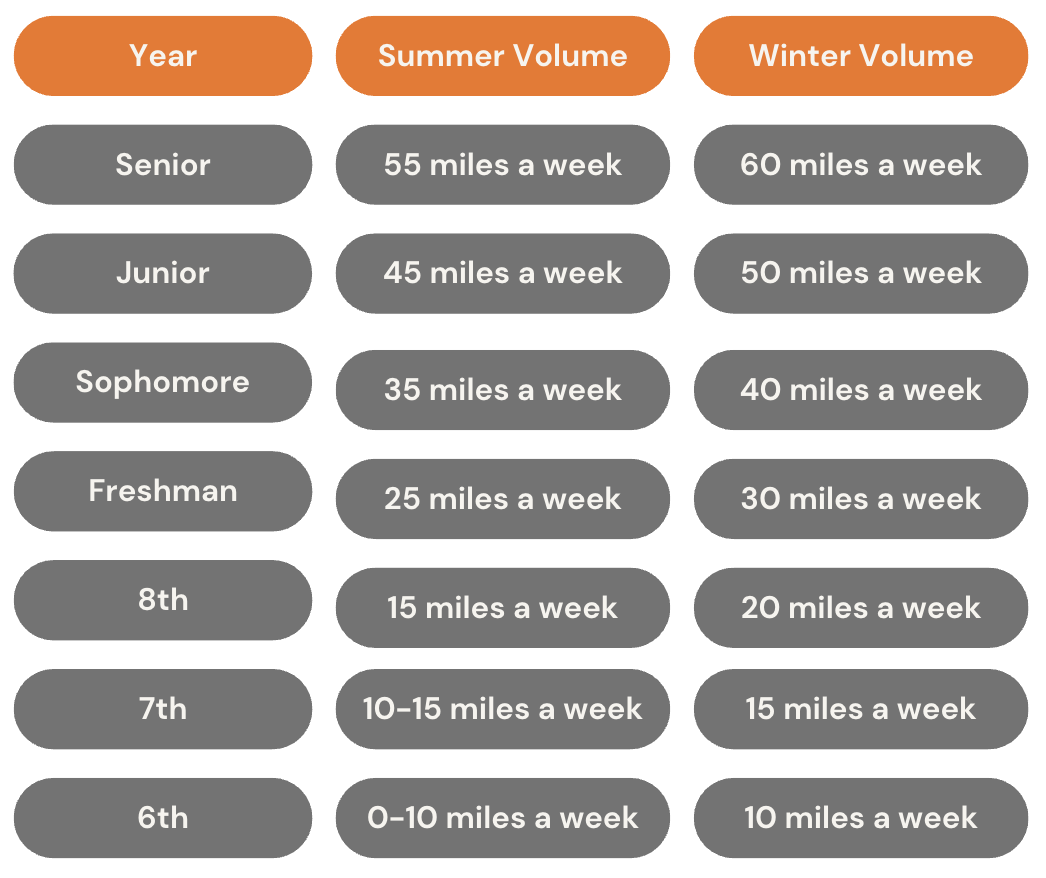

- Suggested progression: 6th grade (15 mi/wk) → 7th (20) → 8th (25) → 9th (30) → Senior (60)

- Goal: Create a culture where running is FUN, not win middle school state titles

- Include speed development, games (ultimate frisbee), and post-run strength work

- Sixth graders don't need to run in summer to have a great first XC season

Coaches and parents want middle school cross country training to be fun and to lead to a lifelong love of running. But to do this, a coach can't simply take high school training and water it down. Nor should they expect a sixth grader to demonstrate the same commitment to training expected of a ninth grader.

My goal in this article is three-fold:

- To explain why a conservative approach to cross country training in the middle school years sets athletes up for success in high school

- Give you a middle school cross country training plan you can follow today, including warm-ups, workouts, and post-run strength work

- Answer the question: What should our real goals be with middle school runners?

Sound good? Let's go!

The Three Goals for Middle School Cross Country (In Order of Priority)

Before we dive into training specifics, we need to be crystal clear about what we're trying to accomplish with 11-14 year old runners. Here are the three goals, listed in order of importance:

Goal #1: Have Fun The number one goal with middle school athletes is for them to have fun. How do you know it's fun? Simple. Do they show up excited to be at practice? And do they leave having had a good time?

Goal #2: Create Lifelong Runners The second goal is for them to have so much fun that they become lifelong runners. We want them running in their 20s, 30s, and beyond—not burned out by age 16.

Goal #3: Set Them Up for High School Success The third goal is to set them up to become solid high school runners. But here's where we need to be careful. This goal is important, but it's also where coaches get into trouble.

Goals one and two should be your primary focus as a coach. When kids have fun and fall in love with running, goal three—high school success—tends to follow naturally. But when coaches focus too heavily on immediate performance and high school preparation, they often undermine the very foundation that leads to long-term success.

What you're about to read might sound conservative compared to what other programs are doing. But it works. When you create an environment where middle schoolers genuinely enjoy training, where they stay healthy and see consistent improvement, where they're part of a positive team culture—that's when the magic happens. The athletes who have the most fun and develop the deepest love for the sport are usually the ones who surprise everyone with their high school performances.

A Quick Story About Long-Term Development

I've coached for over 20 years, with eight of those years at the collegiate level. During my time as recruiting coordinator and assistant cross country coach at the University of Colorado, I realized there are special considerations when coaching middle school runners—particularly middle school girls.

My experience recruiting NCAA Division I athletes was that many of the women who had the best collegiate careers weren't standouts in middle school. Some never ran in middle school and only started running in high school. In contrast, two NCAA cross country champions at CU while I was an assistant coach—Jorge Torres and Dathan Ritzenhein—trained seriously in middle school, and by their freshman year in high school, they were training very hard. Both men went on to make US Olympic Teams.

Here's what this taught me: We need to take a long-term view for these young learners and implement training that will allow a 12-year-old sixth grader to be better as a 15-year-old ninth grader, and even better as an 18-year-old senior.

We also want them to be able to run fast in their 20s, and we want them to become lifelong runners. We want to be especially careful not to overtrain middle school girls given the lack of correlation between middle school success and success in college.

Why Less Is More: Working Backwards with Mileage

Every coach and parent wants athletes to run faster in high school than they did in middle school. But what should a middle school coach do to set this trajectory in motion?

Let's start at the end—the senior year of high school—and work backwards to a runner's sixth-grade year. Here's a simple progression that has the athlete running 60 miles a week the winter before their senior year of track:

Before you say, "Jay—this isn't nearly enough. You just added five miles a season," let me explain the rationale.

First, the sixth grader does not need to run in the summer to have a blast racing their first season of cross country in the fall.

You, the coach, need to have a plan in place so they can come in with "no prior training" and stay injury-free all fall. The middle school training plan we'll discuss includes speed development workouts, playing games, and doing extensive post-run work.

Our goal during these years is for kids to have fun racing while laying the foundation for them to run "real" volume their sophomore through senior years.

Second, we need to think of each calendar year as having four seasons: Summer, Fall Cross Country, Winter, and Spring Track. A high school sophomore who makes 85 percent of summer practices would be at the 35 miles-per-week volume in our progression. But once school starts, they'll likely have weeks at 40 miles as they attend every practice and run faster.

The Car Analogy: Building Complete Athletes

Let's use the analogy of a car to understand what middle school runners need. The heart and lungs, circulatory system, and mitochondria in skeletal muscle make up an athlete's "aerobic engine." Every race distance from 800m on up is primarily fueled by the aerobic metabolism. A middle school athlete racing roughly 3200m most meets needs a solid aerobic engine.

But here's what's counterintuitive: An athlete coming from swimming or soccer may have a big aerobic engine but a weak "chassis." We'll consider the bones, muscles, ligaments, tendons, and fascia the chassis. Just like a fast car with a big engine needs a strong chassis, we need to do chassis strengthening work daily.

Young athletes will "build their engines" faster than they can strengthen their chassis. My friend Mike Smith, who coached at Kansas State University and now coaches at West Point, explained this concept: "Metabolic changes occur faster than structural changes."

For middle school athletes, who often come to running with modest athletic backgrounds, their engines can improve dramatically in just a few months. That means they need to spend significant time on strength training so both their engines and chassis improve at roughly the same rate.

Finally, these athletes need to "rev the engine" most training days by doing strides—short sprints that are faster than race pace.

The Four Elements of Every Middle School Practice

1. Dynamic Warm-up We're not doing static stretching. Instead, we'll do a dynamic warm-up that has the body moving in all three planes of motion. This takes 10-13 minutes and is crucial for injury prevention.

2. The Main Training This could be an easy run, a fartlek workout, running circuits, or speed development work. The key is that we're not trying to replicate high school training—we're doing age-appropriate work that builds fitness while maintaining athleticism.

3. Strides (Most Days) Short sprints that teach athletes to run faster than race pace. These are fun and crucial for developing speed and good running mechanics.

4. Post-Run Strength Work Every day they run, middle school athletes need to do chassis strengthening work. This doesn't mean the weight room—it means bodyweight exercises that improve strength and mobility.

Middle School-Specific Workouts

Running Circuits - Circuits combine short running segments with strength and mobility exercises. Athletes might run 200m, then do squats and lunges, then run another 200m. This builds the engine while strengthening the chassis, but with much less running volume than a traditional workout.

Fartlek Runs - "Speed play" workouts where athletes alternate between "on" (slightly faster) and "steady" (faster than easy pace) segments. We start with 1 minute on/1 minute steady, teaching athletes to run by feel.

Speed Development Days - One day per week devoted entirely to improving max speed. This sets athletes up to be faster at all distances and improves their kick.

The beauty of these workouts is that they build fitness while being inherently fun. Kids love running fast in speed development sessions. They enjoy the variety of circuits. They feel accomplished completing fartlek runs.

The Mental Component: Building Attention Span for Hard Work

Here's something most people miss about middle school training: we're not just building physical fitness. We're building mental fitness too.

When an athlete does a 13-minute dynamic warm-up, then a 15-minute circuit workout, then goes immediately into 15 minutes of post-run work, they've just focused on challenging exercise for 43 minutes straight. That builds their attention span for hard work—a skill they'll need desperately in high school.

We're going to forego killer workouts and let the races be the most challenging days of the week. This is one of the biggest mistakes I see middle school coaches make—they want to train too hard during the week.

The difference with middle school versus high school is that middle school kids can and should race more often. They'll race well if you follow these simple workouts that improve athleticism while building stronger aerobic engines.

Why This Conservative Approach Actually Works

I know what you're thinking: "Jay, other programs are doing more mileage and more intense workouts. Won't we get beat?"

Here's the thing: Yes, you might get beat at the middle school state meet. But that's not the real competition.

The real competition is seeing which programs produce the most high school runners who are still excited about the sport, still healthy, and still improving. The real competition is seeing which programs create lifelong runners who are still running in their 20s and 30s.

We're not trying to create middle school state champions. We're trying to create kids who love running so much that they can't wait to see how fast they can get in high school.

When athletes finish their middle school career, excited to run in high school, when they've stayed injury-free, when they've experienced the joy of consistent improvement throughout each season—that's when you know your conservative approach worked.

The Bottom Line: Trust the Process

Will your team win the middle school state cross country title with this approach? Probably not. They'll probably get beat by teams doing more volume. But six months later, when those other teams' athletes are burned out or injured, your athletes will be showing up to high school practice excited and healthy.

Remember: If you want your athletes to do things they've never done before in high school, you've got to be willing to do things you've never done before as a middle school coach. Take the conservative approach. Focus on fun and developing a lifelong love for the sport. Trust that when kids genuinely enjoy training and racing, the performances follow.

The approach you're about to learn might sound conservative, but it works. Your athletes—and their future high school coaches—will thank you.

Get The Free PDF

Download my complete Middle School Cross Country Training PDF, which includes 5 weeks of daily workouts for different ability levels, warm-up routines, speed development protocols, and post-run strength progressions. Everything you need to keep middle school runners healthy, happy, and progressing.

One final point...

The XC Training System has 24-week plans for every level of athlete on your team. And there are hours and hours of video resources. This PDF is valuable and it’s useful. And...

It only scratches the surface of what’s in the XC Training System. If you like what you see, take some time to check out the XC Training System.

“I have coached for 25 years, and have tried to stay current on training and coaching methodology throughout my career.

I can confidently say the XCTS is the best value and input I've received in my coaching career and was effective both as far as results and injury prevention.

My 25 runner freshman program was 100% on the "no prior training" XCTS plan and for the first time in my coaching career no athlete was injured during the entire season!!!

The top runner set the school record for the 3K and 5K and the team overall did well by historical standards.

The training system for my varsity was greatly influenced by the XCTS. The 16:09 team average at our Divisional meet was the fastest in school history and every member of our team had a PR at Divisional or States. Injuries were much less frequent.

Overall, the team was in the trainer's room less and was highly competitive in the most competitive division in the state of MA.” - Seth Kirby

"The XC Training System is a game-changer" - Liz Schaffer

Check out the XC Training System (XCTS)

About Coach Jay Johnson

Jay Johnson has coached high school, collegiate, and professional runners for over two decades, including three USATF champions in cross country, indoor track, and road racing. He studied kinesiology and applied physiology at the University of Colorado, where he was a member of the varsity cross country team featured in Chris Lear's cult-classic Running with the Buffaloes. His book Consistency Is Key has sold over 20,000 copies. Jay has been quoted in Wired, Outside, and Runner's World, and his YouTube channel has over 2.9 million views.